Ensuring diversity, equity, and inclusion in rare disease organizations requires focused programs that engage all stakeholders. A nine-month project just completed by RARE-X found creating campaigns that raise awareness on how to effectively communicate with physicians and patients and partnering with medical schools to increase interest in students specializing in rare diseases were among the findings.

The project was undertaken to provide a general overview of the rare disease landscape regarding DEI issues and offer recommendations to support RARE-X’s efforts to ensure the long-term development of an inclusive rare disease data platform. It involved a literature review, surveys of patients and caregivers, focus groups, and individual interviews with the broader rare disease ecosystem.

I. BACKGROUND

With the United States’ population becoming increasingly diverse, ensuring principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in every facet of rare disease research has become essential to improving all patients’ quality of life.1 The diagnosis of a rare disease can take years, with patients seeing an average of seven doctors before they receive an accurate diagnosis.2 In addition to the prolonged disease diagnostic odyssey, diversity in the rare disease research field continues to be a great public health concern.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), there are an estimated 25 million to 30 million Americans with a rare disease, with higher incidence and prevalence among ethnic and racial minority groups than the general population.2 These disparities exist for various reasons, including genetic, cultural, and linguistic differences, limited access to care, and socioeconomic and environmental factors.1 Moreover, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), the demographics of the U.S. population is shifting with nonwhites representing more than 50 percent of the population by 2045. As this shift in demographics occurs, there is an increased need to create more diverse rare disease research networks.

A plethora of evidence suggests research networks that lack diversity have several disadvantages: drug outcomes may not be applicable to certain populations and unmet medical needs limit our understanding of differences among minorities, resulting in inappropriate recommendations.3 More importantly, creating a rare disease culture that fosters DEI principles creates an opportunity for all stakeholders to feel supported and thrive regardless of their unique differences. RARE-X, a 501(c)(3) organization, focuses its efforts on the state of the rare disease research field nationally, specifically focusing on multiple rare diseases with an emphasis on increasing diversity among rare disease networks more broadly.

The purpose of this scoping review was to provide a synopsis on DEI in the rare disease space from the perspective of various stakeholders to inform RARE-X’s current and future initiatives.

II. APPROACH

Framework for Achieving Proposed Purpose

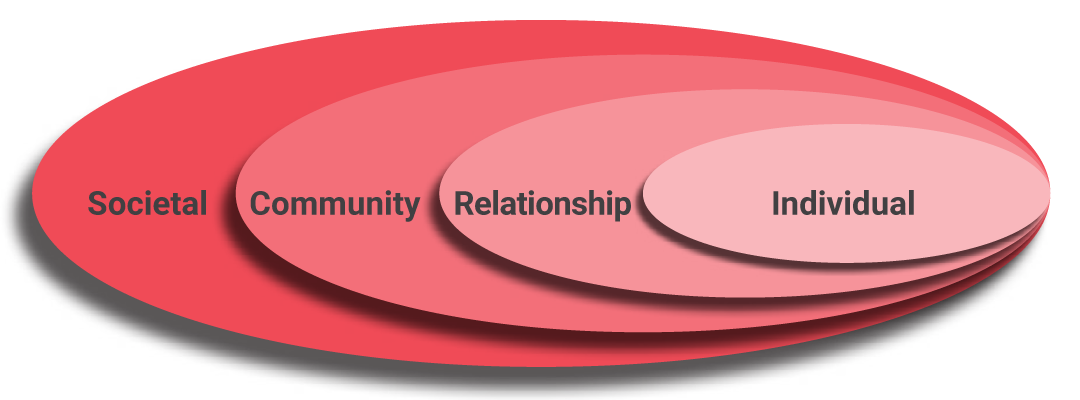

The primary purpose of this nine-month project was to provide a general overview and offer recommendations on diversity, equity, and inclusion within the rare disease field to support RARE-X’s efforts of ensuring the long-term development of an inclusive RARE-X platform. This project focused on addressing levels within the social-ecological model (Figure 1) to maintain efforts for the duration of the project and to address the overall long-term goals of RARE-X. This included formulating strategies to create an advisory council, conducting focus groups and individual interviews, disseminating surveys, and conducting meetings to identify/prioritize overall project strategies.

Figure 1. The Socio-Ecological Model

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention.

http://www cdc gov/ncipc/dvp/social-ecological-model_DVP htm..

To guide our efforts, the advisory board also created a DEI guiding statement clarifying how we defined diversity, equity, and inclusion.

DEI Guiding Statement

Diversity

Our efforts in addressing diversity will constantly evolve. From our approach to surveys, focus groups, and interviews, this work will allow us to add layers of data. Our aim is to approach diversity as we would our nation in regard to one large community with many neighbors that create neighborhoods.

We know the collection of data from national organizations typically address age, sex, and ethnicity/race. Our approach is to take these factors as a base of diversity; listen, learn, and expand upon these for this project and future projects. Community includes factors (such as religion, culture, access, and privilege) that may not fit a checkbox yet make a huge impact on equity and inclusion, which are pillars that create a diverse community.

Equity

We are committed to being impartial and accepting of all participants involved in surveys, focus groups, and individual interviews.

Inclusion

Our philosophy and policy are providing equal access to opportunities for people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized.

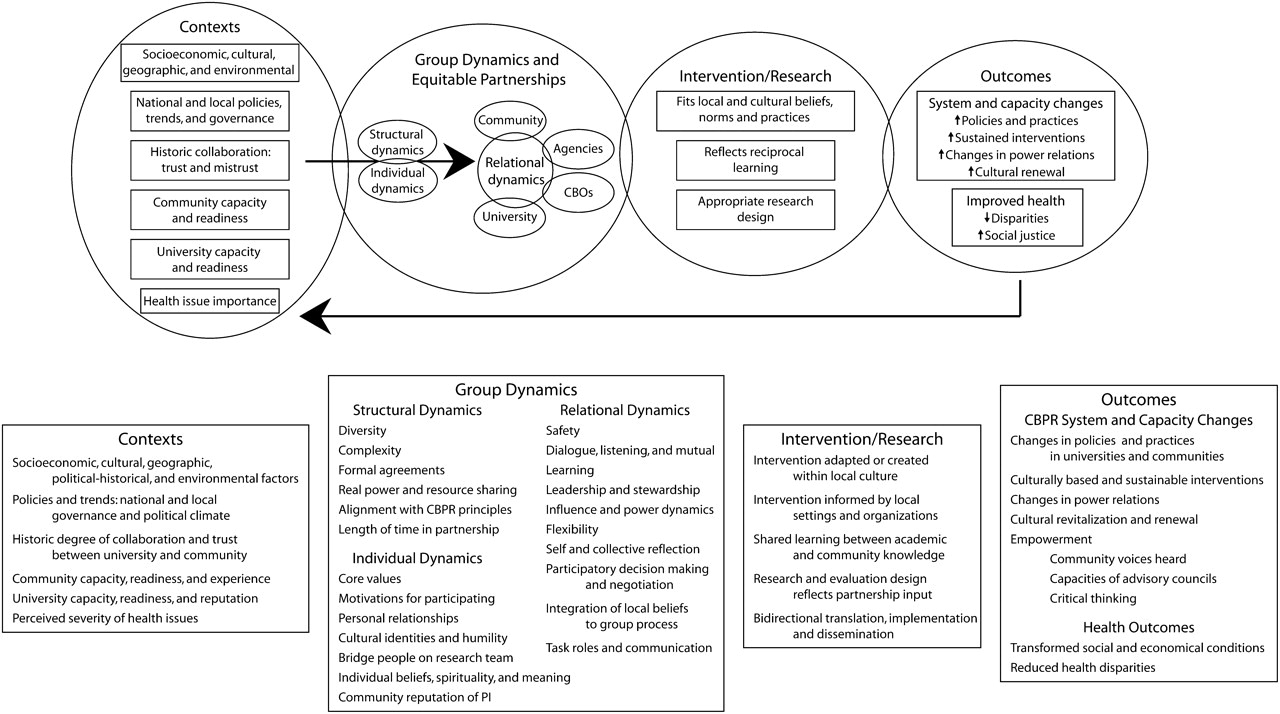

Supporting diversity in rare disease research (clinical trials, data platforms, etc.) requires grassroots efforts using community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods. Figure 2 is an illustration of a CBPR conceptual model that incorporates the dynamic interactions that are imperative to providing opportunities for participants to buy into research methods, actively participate, and sustain meaningful research efforts, ultimately decreasing health disparities overall. We incorporated principles of CBPR with the use of an advisory council with minority and rare disease representation. The advisory council served as the overseer of the project, providing specific guidance to accomplish the overall project Societal Community Relationship Individual purpose. This advisory council also played an important role in the development and submission of the final report. In addition, we hired a community liaison to serve as the liaison between the project team and the larger rare disease community. As we built relationships with community stakeholders and community members, we created a bidirectional dialogue so that efforts were continuously monitored by key constituents.

Figure 2. Conceptual logic model of community-based participatory research

Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036

This project addressed the following specific aims:

Specific aim 1:

Implementation of a nine-month mixed-methods scoping project that will assist in informing RARE-X’s goal of designing an inclusive, demographically representative patient-owned data collection portal in the United States.

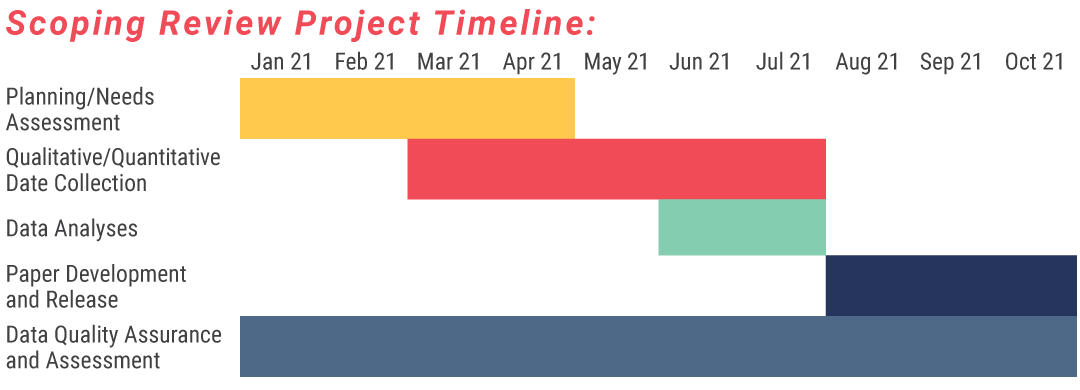

Aim 1a. took place from Jan. 2021 – April 2021. During this time, we conducted the following activities:

1a. A needs assessment via a literature review that addresses the scope of diversity concerns within rare disease, recommendations for addressing these issues, and overall assessment of diversity in rare disease data platforms

- Assembled a list of rare disease stakeholders

- Created a survey that addresses data needs, challenges, diversity concerns, recommendations, and links to potential key diversity stakeholders

Aim 1b. took place from March 2021 – July 2021. During this time, we conducted the following activities:

1b. Conducted quantitative/qualitative (survey, focus groups) data collection to address potential cultural impacts on language, understanding (or lack of) of rare disease, technology limitations, and trust issues within minority communities

- Conducted 1 focus group

- Conducted 13 individual interviews with rare disease stakeholders to highlight some of the concerns they have with regard to data collection, experiences within the healthcare system, and recommendations they may have for an inclusive data platform Aim 1c. took place from April 2021 – Oct. 2021.

During this time, we conducted the following activities:

1c. Provided recommendations based on the quantitative/qualitative data collection to inform future efforts via a guidance paper

- Ongoing data analysis

- Based on the data analysis results, developed recommendations for a guidance paper Aim 1d. took place from August 2021 – Oct. 2021.

During this time, we conducted the following activities:

1d. Developed a guidance paper, lay-term guidance paper, and academic paper for possible journal submission

- Identified potential journals for submission

- Developed the guidance paper

- Started on a potential publication to be submitted in the future

III. LITERATURE REVIEW

Rare Disease Overview

In 1983, the United States passed the Orphan Drug Act to provide sponsors incentives to develop drugs to treat, prevent, or diagnose rare diseases (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2021). This Act prompted the formal definition of rare diseases as a disease or condition that affects less than 200,000 people in the United States. Since this Act was approved, more than 600 drugs have been approved to treat rare diseases (Haffner & Maher, 2006; Murphy et al., 2012). Overall, there are at least 7,000 designated rare diseases that affect about 30 million people across the United States, most of whom are children (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2021). About 80 percent of conditions are genetic and caused by changes in genes or chromosomes. Other rare diseases include infections, rare cancers, and some autoimmune diseases that are not inherited (Miravitlles et al., 2020; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2021).

Miseducation about Rare Diseases

Of great concern is the lack of awareness and education regarding rare diseases, which makes it more difficult to identify symptoms and for patients to receive any available treatments. Much of the confusion surrounding rare diseases is the lack of a clear definition that is widely recognized. While the United States defines rare diseases as a condition that affects less than 200,000 people, the Europea

Union defines rare diseases as a condition that affects less than 5 per 10,000 people, and in Japan, it is 1 in 2,500 people (Richter et al., 2015). This means that the prevalence of a rare disease will differ in each country, limiting the international attention that a rare disease receives and the number of resources in identifying and researching these conditions.

This lack of awareness and education about rare diseases leads to under- and misdiagnosis of these conditions. In 2008, a European survey found that after the occurrence of first symptoms, about 25 percent of patients waited 5-30 years for a diagnosis, but 40 percent of those were incorrect (EURORDIS& Faurisson, 2009). A report from 2013 showed that in the United States, it takes about 8 years to receive an appropriate diagnosis for a rare disease and about 6 years in the United Kingdom (Shire Human Genetic Therapies, 2013). A delay in diagnosis can lead to worsening of symptoms, delays in appropriate treatment, receiving unnecessary medical interventions such as tests and surgeries, and mental and physical deterioration of a patient, all of which can lead to an early death (Budych et al., 2012; Walkowiak & Domaradzki, 2021). Additionally, to receive a proper diagnosis, patients must visit multiple healthcare providers, leading to additional medical costs, which can be prohibitive for those who are under- and uninsured (Zurynski et al., 2017).

To improve education and awareness about rare diseases, many campaigns and initiatives have arisen, including the celebration of Rare Disease Day, and the creation of websites and organizations dedicated to general and specific rare disease information such as the National Organization for Rare Disorders, All of Us, and Black Women’s Health Imperative. However, there is still a lack of awareness about rare diseases among the general population, healthcare providers, families, and patients. This has led to patients becoming self-experts in their rare disease to better advocate for themselves when trying to receive healthcare services. There is great need to better understand barriers to care among those living with a rare disease and improvement in medical education so that healthcare providers are better equipped to serve patients living with a rare disease.

Diagnosing Rare Diseases

Because 80 percent of rare diseases are genetic, genetic testing is one of the most efficient ways to diagnose a condition. Yet, despite scientific advancements and improvements in genetic testing, timely diagnosis remains one of our largest challenges. A delay in diagnosis limits the benefits of an accurate diagnosis such as psychological relief, genetic counseling, access to social and educational services specific for a disease, reduction of unnecessary medical procedures, and access to more tailored medical care (Baynam, 2015; D’Angelo et al., 2020).

In the United States, access to genetic testing can be limited for a variety of reasons including a lack of providers with expertise in rare diseases, excessive testing costs that are not covered by insurance, and long wait times for genetic testing appointments. Barriers to accessing genetic testing are exacerbated for medically underserved communities, including people of color, those who are uninsured or underinsured, people with disabilities, and people from the lower end of the socioeconomic hierarchy (Cooke-Hubley & Maddalena, 2011; National Academies of Sciences et al., 2018). Additionally, most rare disease clinics are located within specialized academic medical centers, which introduces geographic disparities for people living further away from these centers.

There is a great need for people of different races, ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, and from different areas to be included in clinical trials to better understand the barriers they face in diagnosing and treating rare diseases. A lack of diversity among participants in clinical trials and healthcare providers adds additional layers of difficulty in diagnosing rare diseases. The All of Us study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health aims to recruit at least one million people living in the United States to better understand the risk factors for certain diseases and how to better treat them (National Institutes of Health, 2021). This project is based on ideas from precision medicine, which focuses on individual health, and considers each person’s environment, lifestyle, and genetic makeup so that healthcare providers can make customized treatment plans.

Ideally, for patients to receive the most benefits from programs like this, there is a critical need for diversity among healthcare providers who can relate to diverse patient populations.

Table 1 provides a brief overview of rare diseases that affect different populations (Boston Medical Center, 2021). We can use sickle cell anemia to illustrate this concept in action. Sickle cell anemia is an inherited red blood cell disorder where there are not enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout the body. Table 1 shows that this condition is prevalent in both the African American and Mediterranean populations. Having people from these populations participate in clinical trials for sickle cell anemia can help in improving diagnostics and treatment procedures. Additionally, having healthcare providers from the same populations can often provide additional comfort to patients as they are able to receive support from medical providers who share similar identities. These providers can also help to advocate for these patients and raise awareness of these conditions within the healthcare system.

Disparities in Rare Disease Research

In order to create appropriate diagnostics, treatments, and therapies for rare diseases, clinical trials are needed to understand the pathophysiology of the disease and how it affects a person and their health. However, many minority groups are underrepresented in clinical trial studies, including racial and ethnic minorities, such as Black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian (King, 2002; Shavers et al., 2001; Tejeda et al., 1996). Women, those living in rural areas, the elderly, and those living with disabilities and chronic illnesses (Murthy et al., 2004) are also often underrepresented. Potential reasons for lower representation in clinical trials include distrust of the medical system and research studies rooted in historic and present-day mistreatment stemming from racism, ableism, lack of invitation to join studies, lack of awareness, cultural barriers, language and linguistic differences, and access to studies (Feyman et al., 2020).

Lack of diversity in clinical trials restricts the knowledge that can be gained on how to better address and treat rare diseases, hinders the ability to test efficacy and safety of new treatments, and limits the generalizability of study findings to broader populations, which can continue to widen the gap in existing health disparities among minority populations (Taylor & Wright, 2005). For example, if Black people are underrepresented in a clinical trial examining the effects on a specific drug to treat a rare disease, the results from the study may not reflect the impact the drug will have on this community if released to the public. Additionally, lack of diversity in clinical trials limits the evidence-based information available to patients and their caregivers that may be beneficial in making decisions about the management of symptom relief (Andersen, 2012; Forsythe et al., 2014).

Previous research has shown that there are many reasons why people from minority groups do not feel comfortable participating in clinical trials. These include distrust of researchers and healthcare providers, fear of experimentation, and logistical concerns including lack of transportation, financial constraints, lack of knowledge about studies and their benefits, and language barriers (Amorrortu et al., 2018; Keruakous et al., 2021; Mills et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Torres et al., 2021; Schmotzer, 2012). While many researchers understand the importance of recruiting diverse study participants, many questions remain on how this can be done.

Below is a list of ideas on how to engage diverse populations in clinical trials (Otado et al., 2015).

- Establish study sites within communities of interest that are closer to the people being recruited.

- Hire study staff from target communities to build trust with participants.

- Build trust between study staff and community healthcare providers. These relationships can offer additional support to participants and affect participants’ willingness to participate and adhere to treatment regimens.

- Build flexibility into scheduling appointments and visits to include nights, weekends, and times/days that do not conflict with business commitments.

- Provide transportation to study participants.

- Offer fair compensation.

- Increase community outreach recruitment efforts with mass mailings, phone calls, etc.

- Conduct pre-visit phone calls/outreach to serve as reminders and provide additional information to participants.

- Conduct post-visit phone calls/outreach to see if the participant has any concerns or questions after the study visit.

- Invest time and money into communities of interest to develop trusting relationships and improve recruitment efforts. • Engage with healthcare providers from all fields including health departments and federally qualified health centers that might see higher proportions of target populations.

- Provide study materials in native languages of the target population, in easy-to-read language, and in a variety of formats, i.e. print, large print, audio, electronic, and screen reader compatible.

- Ensure that study staff are trained to actively listen to participants, are fluent in the language of the target population, and have attended diversity and implicit bias training.

Resources to Help Recruit Minority Populations

- Faster Together – An eight-module, one hour course that focuses on topics including Understanding the Need for Diversity in Clinical Research, Barriers and Facilitators to Participation, Community Engagement Strategies, pre-screening, consent, and retention. Learners work at their own pace. Available at no cost through the online learning platform Coursera. https://www.coursera.org/learn/recruitment-minorities-clinical-trials

- Enhancing Minority Participation in Clinical trials (EMPaCT) – mission to increase recruitment and retention of racial/ethnic minorities into therapeutic clinical trials with the ultimate goal of reducing cancer-related health disparities. https://nimict.com/tools/enhancing-minority-participation-in-clinical-trials-empact/ Stakeholder Engagement to Address Disparities in Rare Disease Research When designing research projects, many researchers rely on information gleaned from academic journals. However, research shows that engaging patients and other stakeholders in the design and implementation of a research study can help to address the lack of diversity in rare disease clinical trials (Forsythe et al., 2014). Stakeholder engagement in the dissemination of research results can also aid in creating materials that can be easily absorbed by patients and caregivers to guide the decision making process in managing symptoms or treating disease.

Organizations Focused on Improving Diversity in Rare Disease Research

- All of Us Research Program

- Black Women’s Health Imperative – Rare Disease Diversity Coalition

- Every Life Foundation for Rare Diseases

- Sickle Cell Disease Association of America, Inc

- Healthy African American Families in Los Angeles County

- National Organization for Rare Disorders, Inc. (NORD)

- Rare Action Network

- The Rare Disease Diversity Coalition

- Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network

Rare Disease Registries

To mitigate barriers seen in accessing healthcare and clinical trials, patient registries are being utilized to facilitate communication and relationships between industry, scientific researchers, clinicians, community organizations, patients, and caregivers (Boulanger et al., 2020; Fink et al., 2017; Maccarthy et al., 2019). Additionally, patient registries can help facilitate the development and implementation of clinical trials, improve patient care, and support healthcare management (Kodra et al., 2018; McGettigan et al., 2019). With patient registries, data for certain people or populations can be collected over time, to allow for additional follow-up and observations. Patient registry frameworks can vary by purpose but generally include (1) public health and epidemiological disease registries; (2) clinical registries that gather physician-entered information about a patient’s disease, treatment, and symptom management; (3) product registries, which capture data on the efficacy and safety of therapeutic and pharmaceutical products; and (4) natural history registries that generate patient-reported data to document the characteristics of a condition (Boulanger et al., 2020; D’Agnolo et al., 2015; Gavin, 2015; Kodra et al., 2017).

A lack of diversity among patients represented and barriers to accessing these registries can limit the impact that they can have on improving drugs and other therapeutics for rare diseases. The goal of this project was to explore opinions about improving diversity within the rare disease space and patient registries among patients, caregivers, health care professionals, and other stakeholders within the rare disease field.

Table 1. List of Rare Diseases that Affect Different Minority Groups (Boston Medical Center, 2021)

Ethnicity Rare Disease

African American Alpha – Thalassemia

Amylodosis

Beta – Thalassemia

Cystic Fibrosis

Lupus

Sarcoidosis

Sickle Cell

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy

Ashkenazi Jewish Canavan Disease

Cystic Fibrosis

Familial Dysautonomia

Gaucher Disease

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Tay-Sachs Disease

Asian Alpha – Thalassemia

Beta – Thalassemia

Cystic Fibrosis

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

European Cystic Fibrosis

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

French Canadian Tay-Sachs Disease

Cystic Fibrosis

Hispanic Tay-Sachs Disease

Cystic Fibrosis

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Mediterranean Alpha-Thalassemia

Beta-Thalassemia

Cystic Fibrosis

Sickle Cell Disease

RESULTS

Demographics Questions

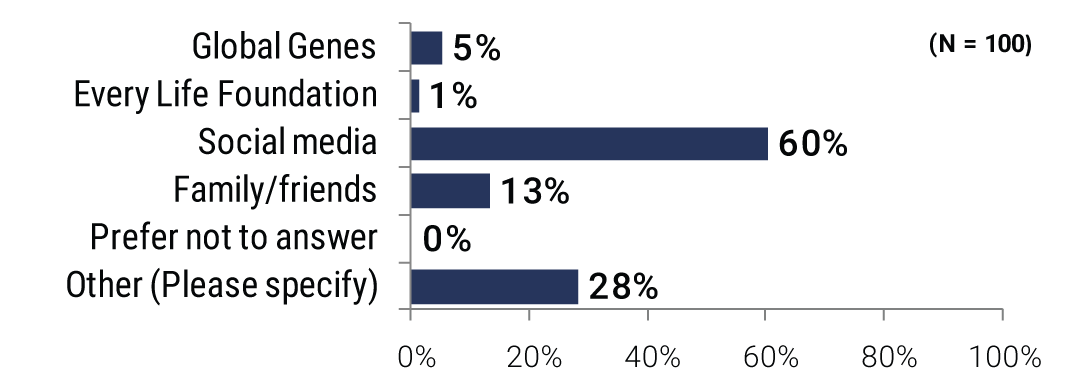

1) How did you find out about this survey? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

When participants were asked how they found out about the DEI survey, the majority of them (60%) referred to social media, which is the main method we used to promote the DEI survey. 28% of participants found out about the DEI survey through other means, including RARE-X, our research team, rare disease patient organizations, and groups such as Pallister Killian Syndrome group, IDefine Organization, and BPAN Warriors.

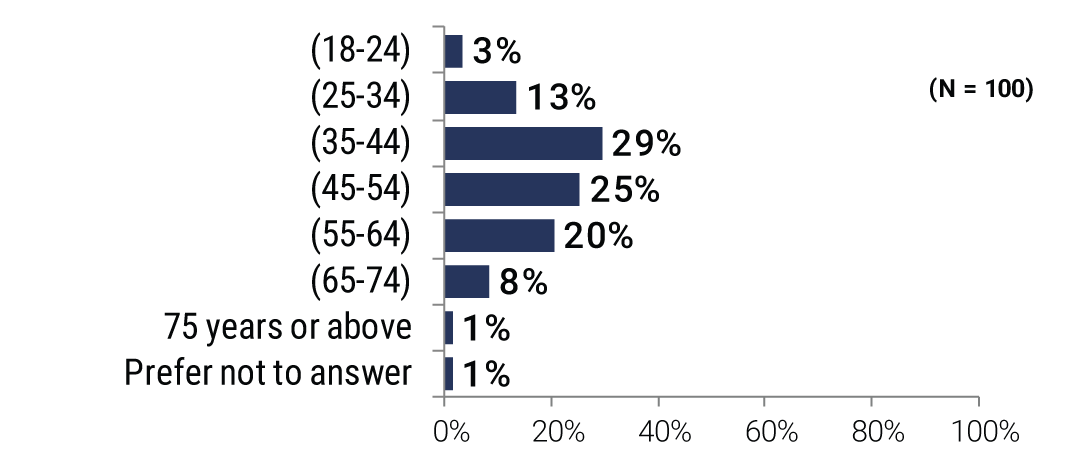

2) Which category below includes your age?

The majority of participants (29%) were of the age category (35-44). 25% of responders were between 45 and 54 years old, while 20 % were between 55 and 64 years old. Only 1% of respondents were 75 years or above.

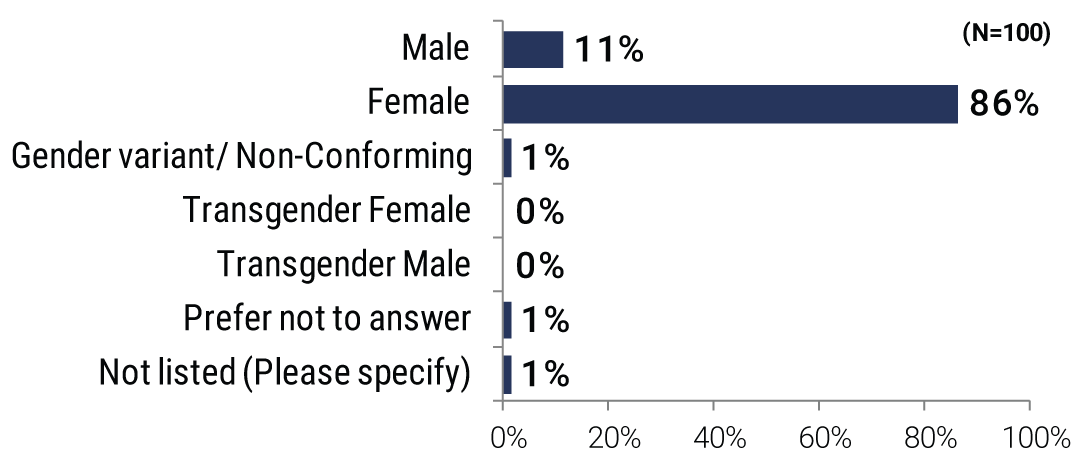

3) How do you describe your gender identity? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

Most of the respondents to the DEI survey (86%) were females. 11 % of respondents were males. 1% classified themselves as Gender variant/ Non-conforming, while 1% classified themselves outside of the given categories.

4) Which of the following categories describe you? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

The majority (63%) identified themselves as White, while (17%) identified themselves Black, African American, or African.

5) What is the highest degree or level of school you have completed?

The majority (46 %) of the survey respondents completed master’s, professional, or doctorate degrees, while (21%) completed their bachelor’s Degree.

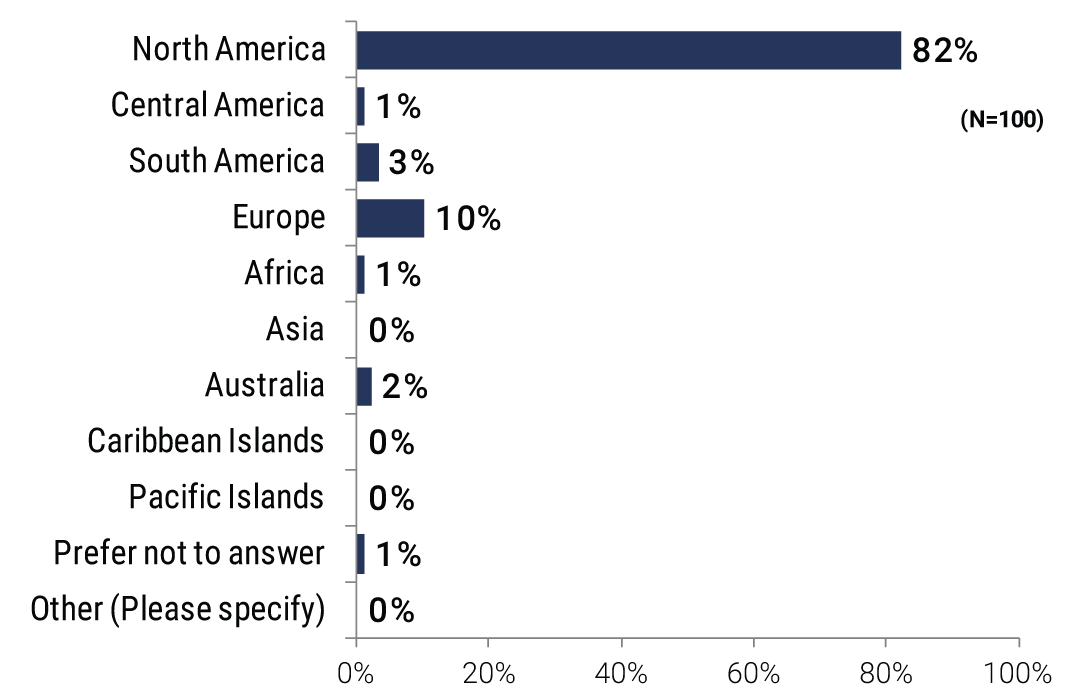

6) Where do you live?

Most participants (82%) live in North America. 10% of participants live in Europe. We received the least responses from people living in Central America (1%), South America (3%), Africa (1%), and Australia (2%).

7) If you live in the United States (U.S.), in which state or territory do you reside?

Out of the 82 responders who live in North America, the majority (16%) reside in the state of Alabama. (7%) of the responders reside in Texas, (6%) in Massachusetts, (5%) in Florida, (5%) in Georgia, (5%) in Illinois, (4%) in Ohio, (4%) in Idaho, (4%) in Pennsylvania, (4%) in Washington, (4%) in Virginia, (2%) in Arizona, (2%) in California, (2%) in Kentucky, (2%) in Maryland, (2%) in Wisconsin, (2%) in Michigan, (1%) in Connecticut, (1%) in Indiana, (1%) in Iowa, (1%) in Kansas, (1%) in Louisiana, (1%) in Maine, (1%) in Nebraska, 1 % in New Jersey, (1%) in New Mexico, 1 % in New York, (1%) in North Carolina, 1 (%) in North Dakota, (1%) in Oklahoma, (1%) in Tennessee, (1%) in Utah, (1%) in Wyoming. (2%) don’t live in the U.S. We received no responses from individuals residing in the rest of the U.S. states or in the main five U.S. territories.

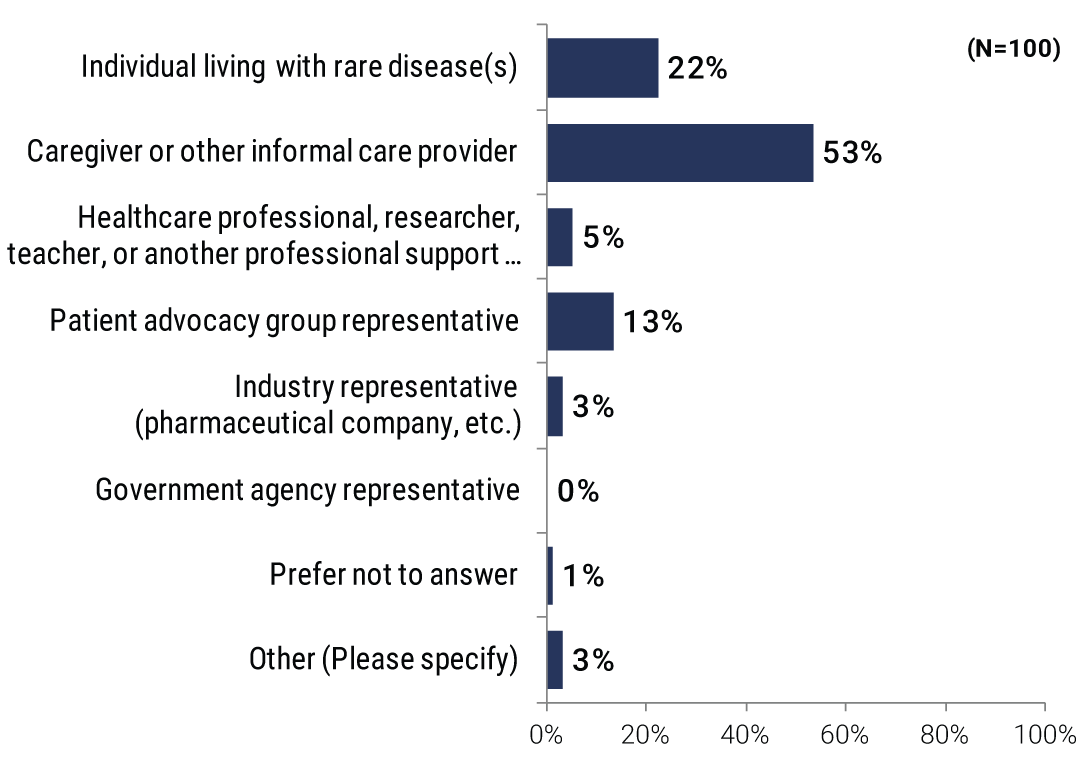

8) Please indicate how you primarily serve (or identify yourself) in the rare disease community.

Responses were mostly (53%) from caregivers or other informal care providers—followed by responses from individuals living with rare disease(s) (22%). 13% of the responders were PAG representatives, 5% healthcare professionals, researchers, teachers or other professional providers, and 3% industry representatives. 3% chose other and explained that they serve the rare disease community in more than one role.

9) What was your total household income before taxes in 2019?

10) Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan? (This includes health insurance through employment, purchased directly, and government programs like Medicare/ Medicaid/ Obamacare.)

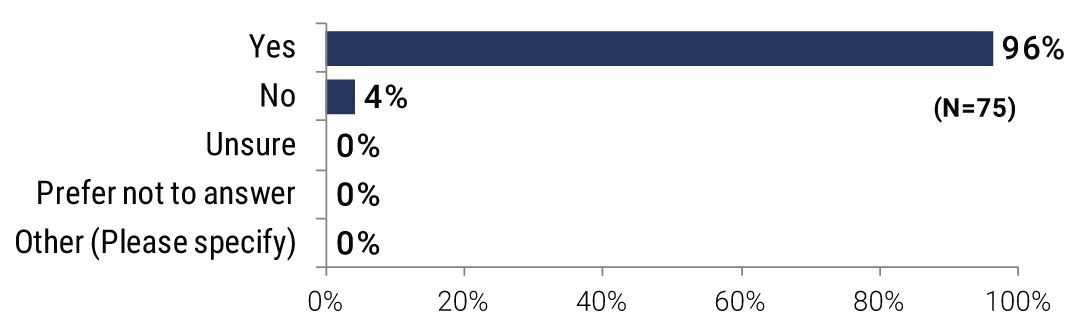

We asked the above two questions #9 and #10 to 75 participants who identified themselves as individuals living with rare disease (s) or caregivers or other informal care providers. In 2019, 19% of respondents had a total household income of (50,000-74,999), 15% had a total household income of (100,000-149,999), and 15% had a total household income of (35,000-49,999). 96% of respondents were covered by health insurance while 4% weren’t.

Main Questions

First Version of the Survey (Audience: Individuals living with rare disease(s), or caregivers or other informal care providers)

11) Do you think there should be more diversity in rare disease research and advocacy?

The majority of respondents (75%) think there should be more diversity in rare disease research and advocacy. 20% were unsure and (3%) don’t think there should be more diversity. 3% chose other where one respondent stated, “Our disease has a very diverse patient group.”

12) What do you think the reasons might be behind the lack of diversity? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

When respondents were asked to choose all the possible reasons behind the lack of diversity, the vast majority (90%) think that limited knowledge of rare diseases is a reason; 62% think lack of educational resources is a cause, and 51% think lack of access to medical care is a reason. 42% of respondents chose cultural and religious beliefs, and 37% chose lack of trust as reasons for the lack of diversity. 4% chose other and quoted reasons like, “lack of understanding of impact of disease, “researchers are not diverse themselves,” “racism in healthcare,” and “lack of referral for genetic testing.”

13) What should patient organizations do to ensure the participation of a diverse rare disease population? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

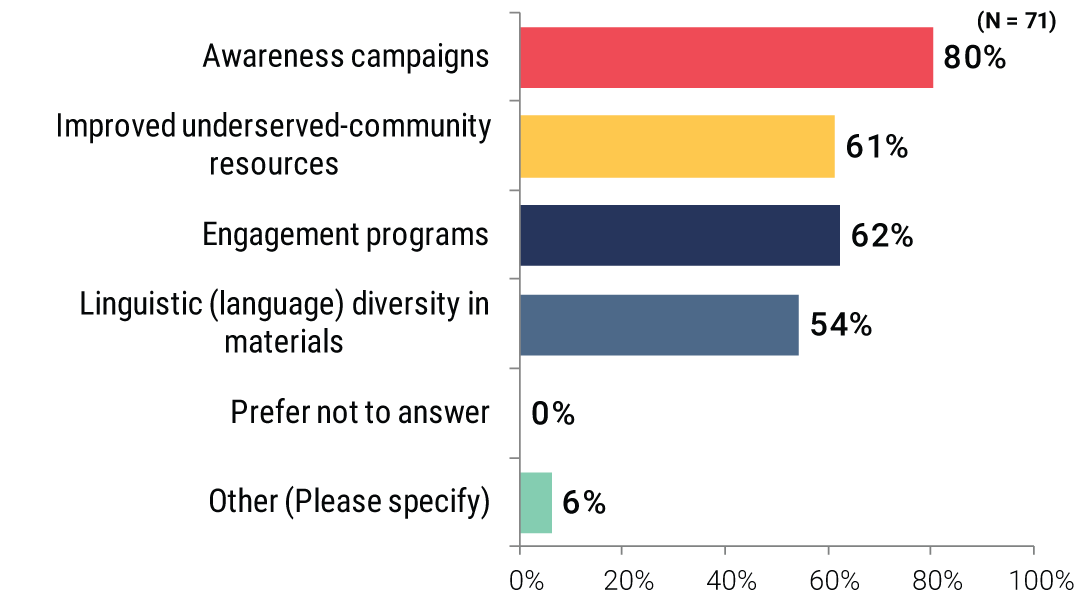

When we asked participants about the methods patient organizations should take to improve diversity in the rare disease population, the most popular response (80%) was that people think awareness campaigns should be carried out to ensure diversity, 62% chose engagement programs, and 61% chose improved underserved-community resources as ways to increase diversity. 6% chose other and suggested ways such as providing a resource for caregiving, investing significantly in raising awareness especially among the medical community, advocacy and outreach for marginalized patients with specialty doctors/clinics (hold doctors and clinics accountable), political advocacy to ensure all people are receiving equitable treatment and opportunity for healthcare coverage (among other health alignment needs – access to housing, food, education etc.), and better referral and access to genetic testing.

14) Would you be willing to share health information in the RARE-X database?

Most of the respondents (79%) are willing to share their health information or the information of the individuals they are taking care of in the RARE-X database. 17% were unsure, while 4% wouldn’t.

15) Are you comfortable entering health information into the database or do you need help from your providers?

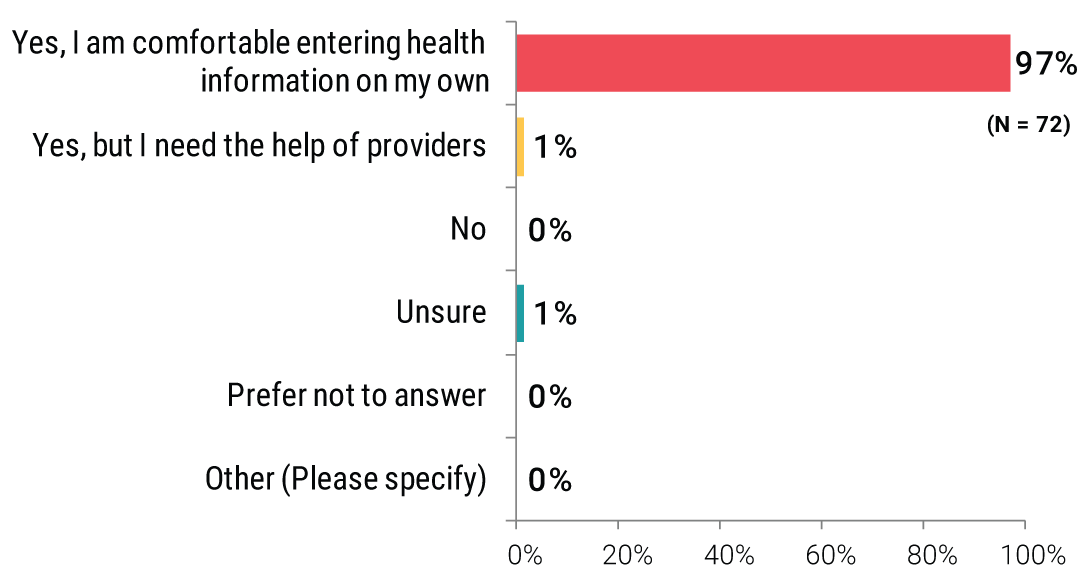

Almost all of the respondents (97%) are comfortable entering health information into the database on their own. Only 1% needs the help of providers to enter data into and 1% is unsure.

16) What are the main outcomes you want to see by sharing health information in the database?

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

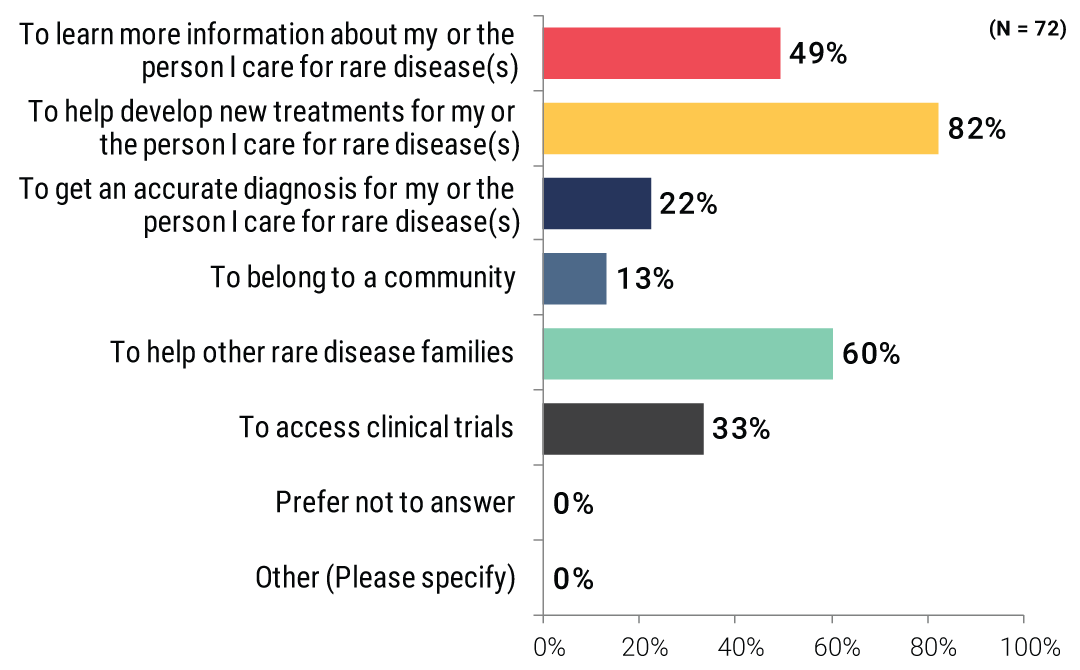

Respondents were given a list of outcomes they wanted to achieve by sharing their health information or the information of the person they care for in the RARE-X database. The majority (82%) hoped that by sharing information, this would help develop new treatments for the rare diseases they are affected by, and 60% wanted to help other rare disease families with the shared information. 49% chose the outcome of learning more information about the rare diseases they are affected by, 33% hoped to access clinical trials, 22% wanted to get an accurate diagnosis while only 13% chose the option of belonging to a community.

17) What are the main concerns you have about sharing health information in the database?

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

Respondents were asked to report their concerns, if any, about sharing health information in the RARE-X database. The most popular responses were related to concerns around privacy where (47%) were concerned about data security and (47%) were concerned about confidentiality. 29% had no concerns, (16%) were concerned about the lack of treatments for the rare diseases that affect them or affect the individuals they are taking care of, and (9%) reported the lack of trust as a concern for data sharing. (7%) were worried about social stigma and (7%) reported their worries about the possibility of inputting incorrect information. The least frequently occurring responses were concerns connected to previous bad experience (1%) and concerns that data sharing is not helpful (1%).

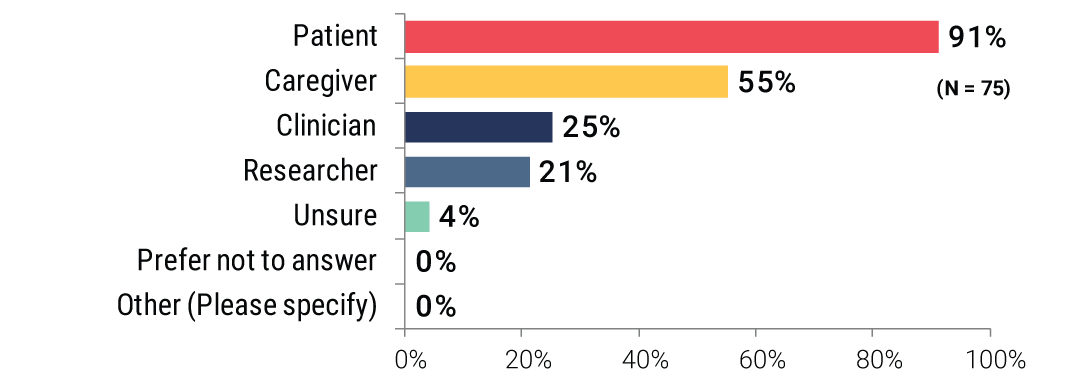

18) In your opinion, who should be the owner of a patient’s health information? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

This question addressed the participants’ thoughts about the ownership of a patient’s health information. The vast majority (91%) of respondents think the patient is the owner. 55% think the caregiver should be the owner, 25% chose the clinician as the owner, 21% believe the researcher must be the owner, and 4% were unsure.

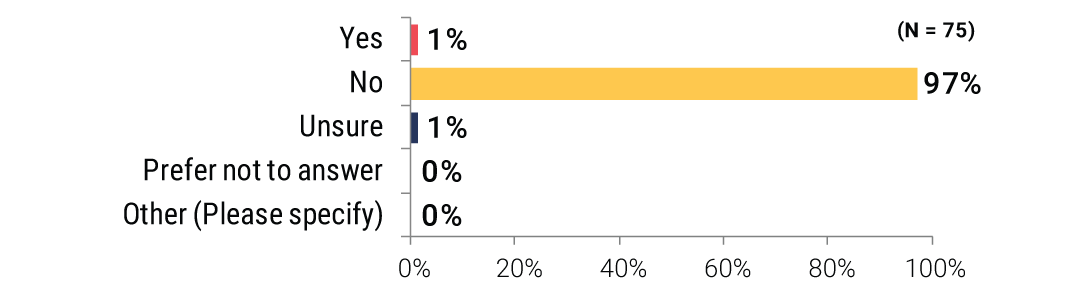

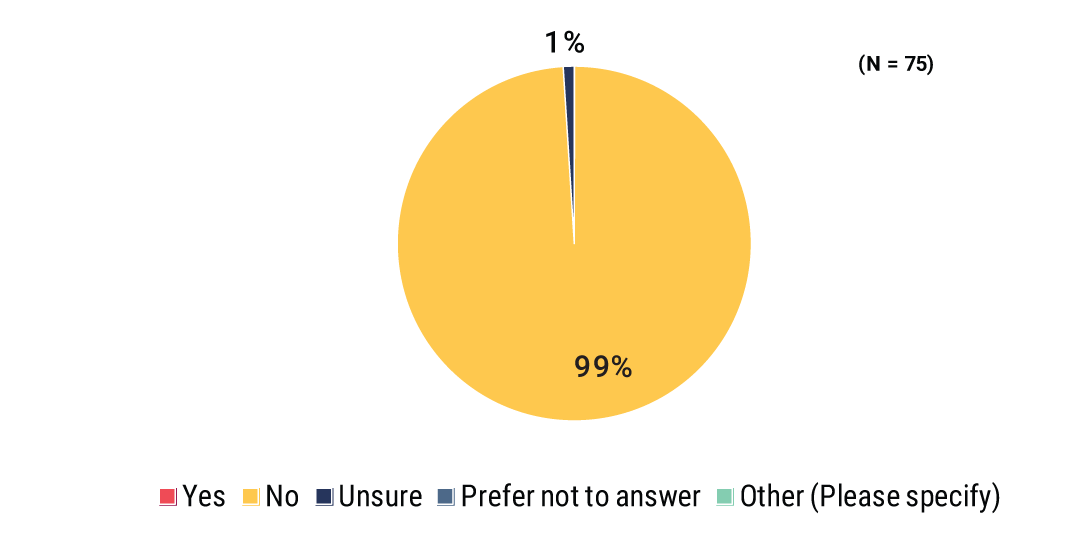

19) Do you have any cultural or religious beliefs that may affect your decision to participate in the database?

20) Do you have any language concerns that may affect your decision to participate in the database?

Questions 19 and 20 addressed cultural or religious beliefs, and language concerns of respondents that could influence their decision to participate in the RARE-X database. Majority of respondents (97%) reported no influencing cultural or religious beliefs and 99% reported no language concerns (99%) when it comes to decisions regarding sharing information in the RARE-X database.

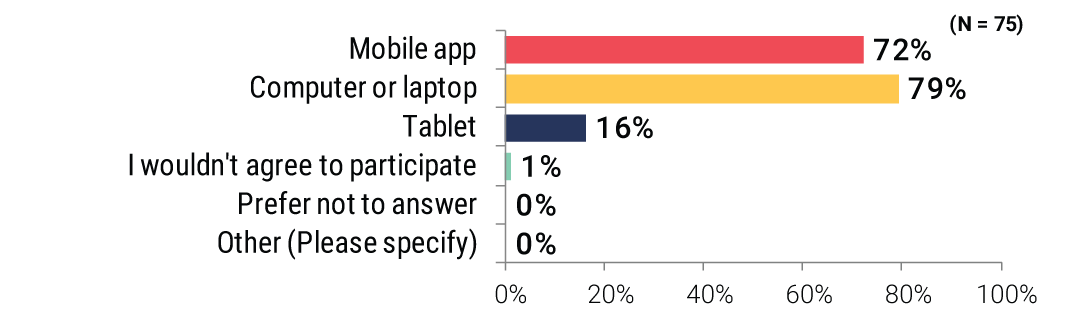

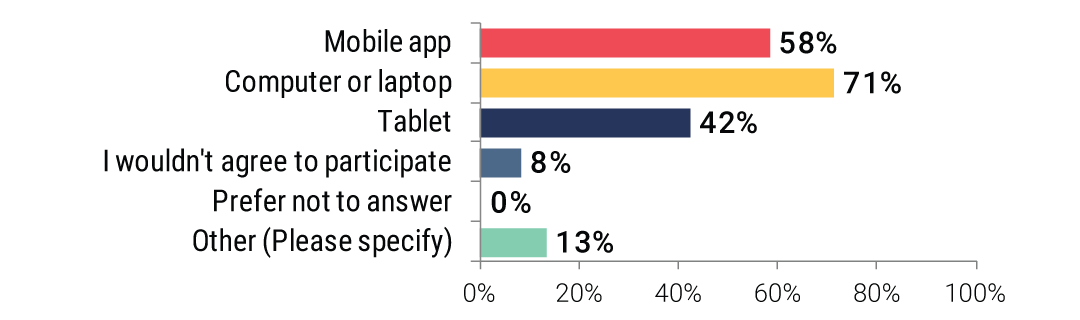

21) How would you like to access the database? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

79% of participants wanted to access the RARE-X database via a computer or a laptop, and 72% would like to access the database using a mobile app. Only 16% chose a tablet.

22) Do you have any suggestions from your experience to ensure the success of the database?

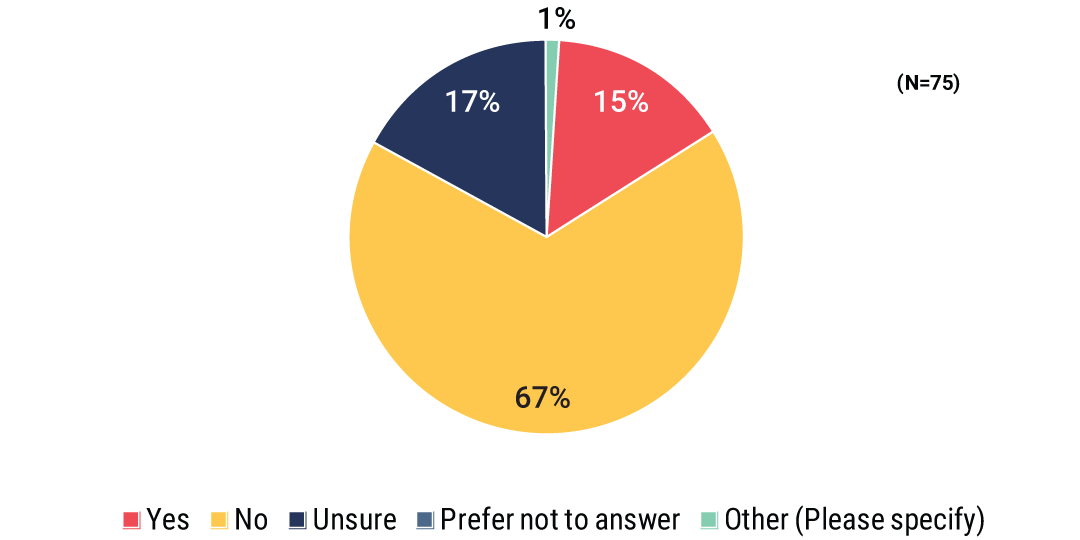

We asked participants if they have any suggestions from their experience that RARE-X should implement to ensure the success of the database. 67% of the respondents had no suggestions, 17% were unsure, and 15% chose yes and quoted recommendations such as the following:

“Easy to answer questions, short surveys – better to have more that are short than fewer that are long.”

“Keep the burden low (as few Q&A as possible), return aggregate data to participants in real time, let the disease community and/or participants know how frequently their data has been accessed, engage with participants to ensure they update their data annually.”

Get genetic reports from as many participants as possible.”

“Regular contact, reminders to update data, communicate value of database to patients – (need to know what’s in it for me).”

“Allow for general surveys and surveys specific for a particular rare disease. Allow patients to give access to de-identified data to a wide range of groups, for example academia, pharmaceutical companies etc.”

“There needs to be the ability to crosstalk with other databases. Avoid the silos and come together collectively for what is best for the patient.”

“For now everything is perfect, but we had problems in finding the link to load the data. It would be perfect if you find a “button” with a shortcut.”

“Needs of patients and patient advocacy groups MUST align and be supported by RARE-X’s strategy. For patient groups with existing registries, will the group receive financial and organizational support for sharing data or helping to recruit patients to RARE-X? Efforts should not be duplicated.”

“In order to be more assertive, it would be very important to plan an online research not only for identifying diagnosed patients but also reaching undiagnosed people who are seeking for an answer.”

“Approach top companies with sustainability agendas like SAP to support you and advocate for you.”

“In order to be more assertive, it would be very important to plan an online research not only for identifying diagnosed patients but also reaching undiagnosed people who are seeking for an answer.”

“Transparency around the purpose of data collection, sharing practices, and what happens to the data after it is provided will help to build trust with patient communities.”

Second Version of the Survey (Audience: health care professionals, researchers, teachers, or other professional providers working with the rare disease community, representatives of rare disease patient advocacy groups, industry, and government agencies, and individuals working in the rare disease and diversity field)

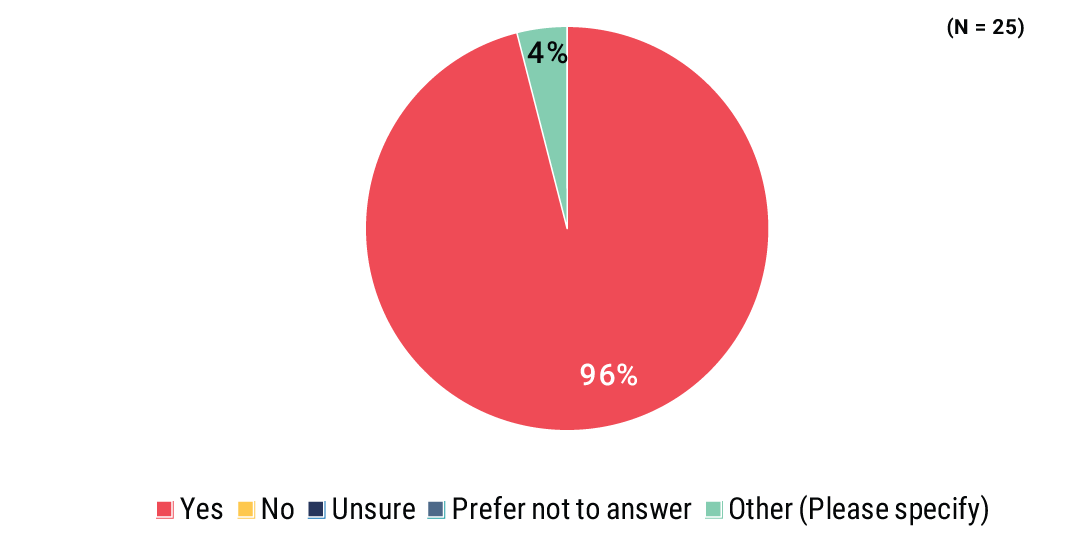

23) Do you think there should be more diversity in rare disease research and advocacy?

The vast majority (96%) of the respondents think there should be more diversity in rare disease research and advocacy. Only 4% chose other and explained that this depends on what the research and advocacy is dedicated to.

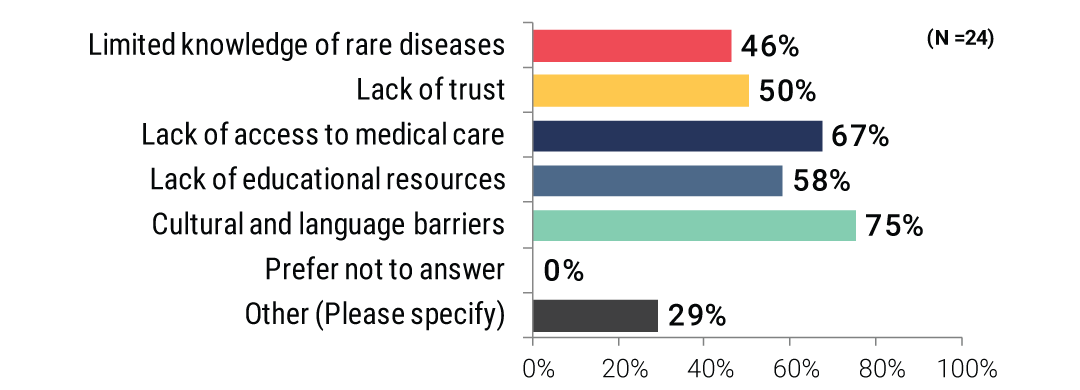

24) What do you think the reasons might be behind the lack of diversity? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

Regarding the possible causes of lack of diversity, the most frequently occurring response (75%) is cultural and language barriers. 67% of the respondents referred to lack of access to medical care, 58% referred to lack of educational resources, 50% referred to lack of trust and 46% referred to limited knowledge of rare diseases as reasons behind the lack of diversity. Respondents who chose other (29%) listed reasons, such as socio-economic barriers, financial and practical barriers, quality of medical care, small population of rare disease patients, lack of outreach, and the social determinants of health such as food, housing, employment, etc.

25) What should patient organizations do to ensure the participation of a diverse rare disease population? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

When we asked participants about the actions patient organizations must take to ensure diversity in the rare disease population, 83% chose improved underserved-community resources, and 71% chose engagement programs. Awareness campaigns and linguistic diversity in materials were equally chosen by respondents (58%). 21% of the respondents suggested other actions to improve diversity, including, physician and caregiver education, supporting, learning and allying with advocates who focus on health disparities, creating a collaborative to ensure that DEI is being addressed by all nonprofits, and collaborating more with community resources already in place — Case Coordination.

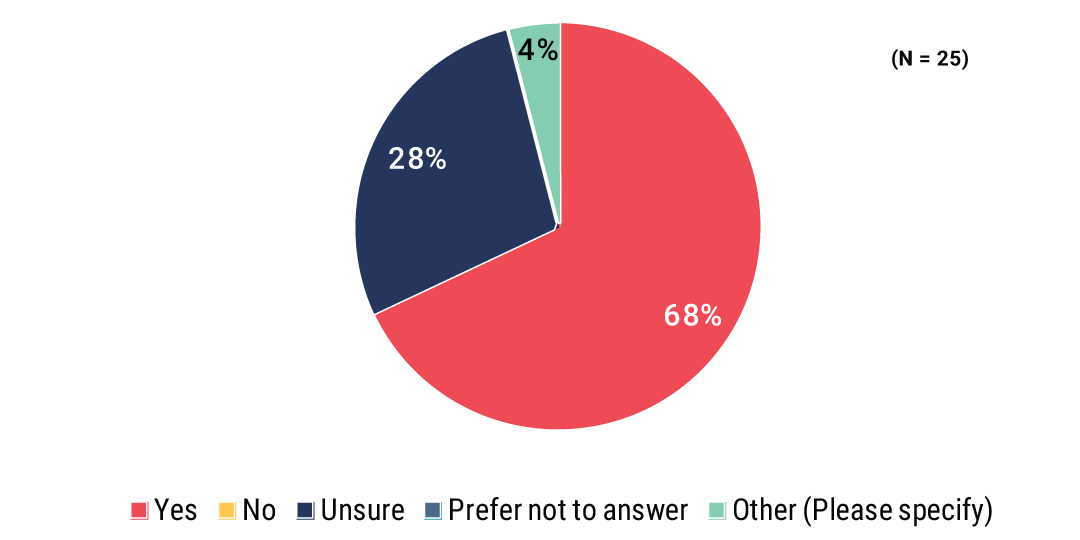

26) Would you use the RARE-X database?

Most of the respondents (68%) reported they would use the RARE-X database while (28%) were unsure. Only (4%) chose other and explained that this depends on how the data is going to be used, the trustworthiness of the RARE-X sponsorship partners, and if patients will be compensated for contributing to the database.

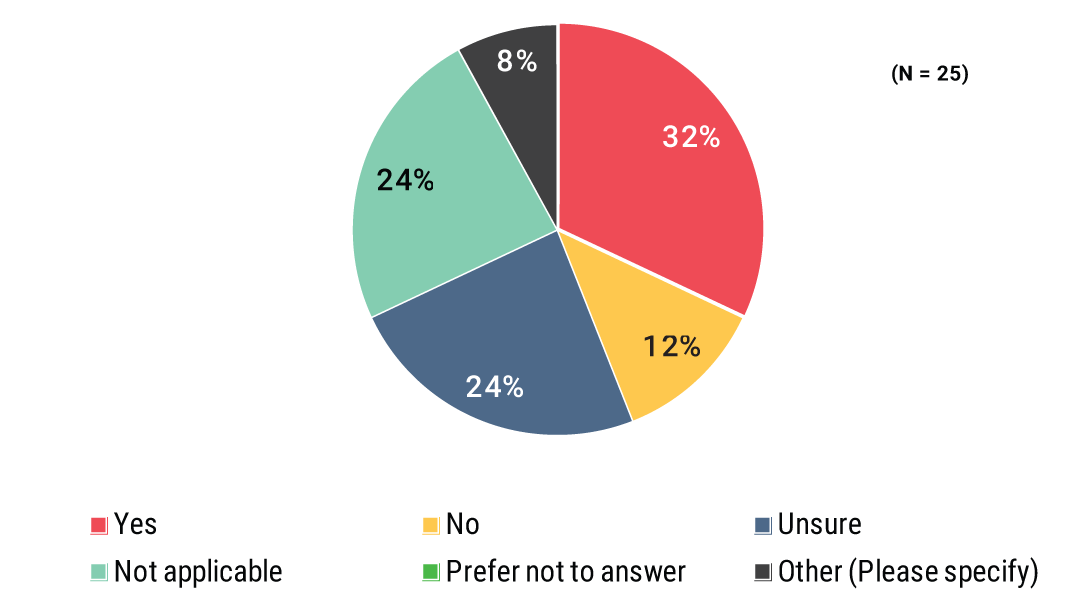

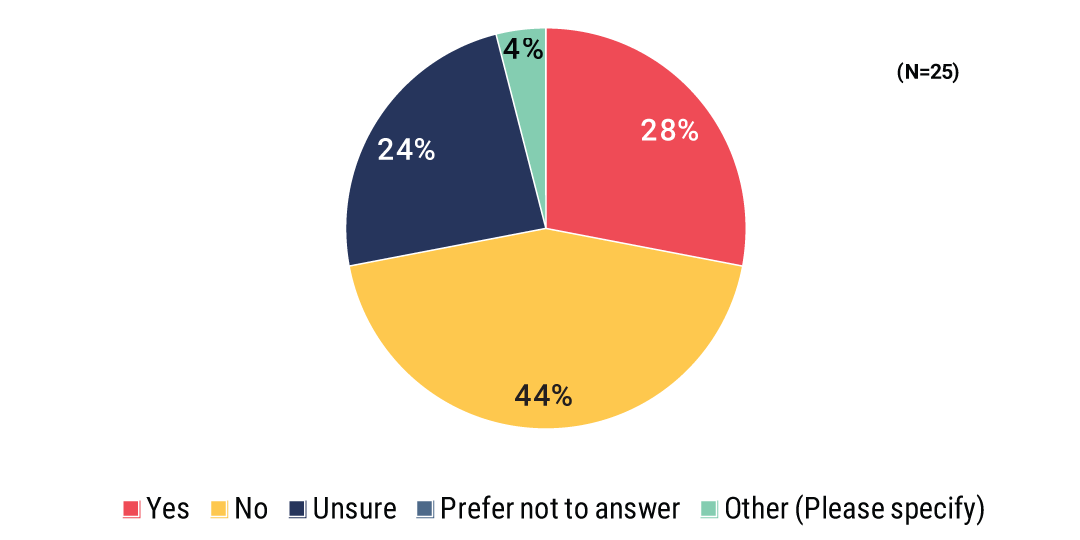

27) Would you be willing to share your rare disease patients’ health information in the database?

32% of the participants were willing to share their rare disease patients’ health information in the database, 12% weren’t, 24% were unsure, and 24% reported that this question doesn’t apply to them.

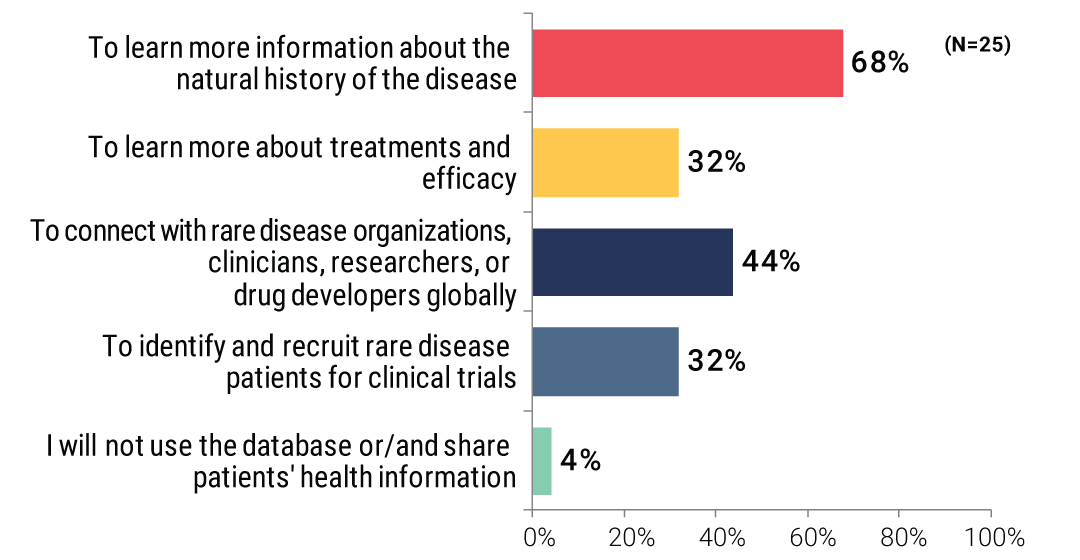

28) What are the main outcomes you want to see by sharing your patients’ health information or/and using the database?

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

Regarding the outcomes the respondents want to achieve by sharing patients’ health information or/and using the RARE-X database, most of the respondents (68%) hoped to learn more information about the natural history of the disease, and 44% wanted to connect with rare disease organizations, clinicians, researchers, or drug developers globally. Learning more about treatments and efficacy, and identifying and recruiting rare disease patients for clinical trials were equally chosen by participants (32%).

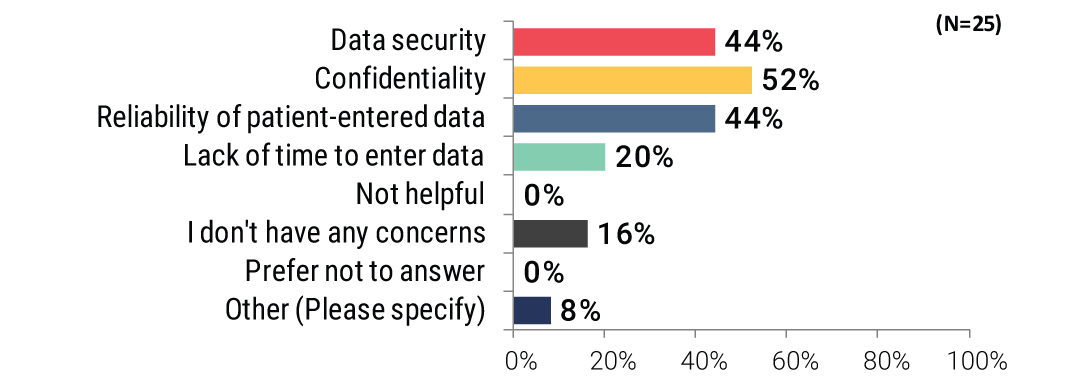

29) What are the main concerns you have about sharing your patients’ health information or/and using the database?

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

When we asked this audience about their concerns around sharing health information or using the RARE-X database, their most popular responses were confidentiality (52%), data security (44%) and reliability of patient entered-data (44%). This is similar to the top concerns individuals with rare diseases and caregivers reported which were data security and confidentiality. (20%) were concerned about the lack of time to enter data and (16%) didn’t have any concerns. (8%) chose other and explained that they didn’t trust how the database will be using the data, and that they aren’t comfortable with rare disease patients providing their data for free.

30) Patients with rare diseases or caregivers will enter health information into the database, do you have any concerns about that?

When respondents were asked if they have any concerns about patients or caregivers entering health information into the database, most of the respondents (56%) had none. 24% were unsure, and 12% had some concerns, such as, bias, error, or inaccuracy of the data. 8% chose other and one respondent quoted, “as long as patients/caregivers are trained in a way that works for them — language, culturally appropriate, not over burdensome.”

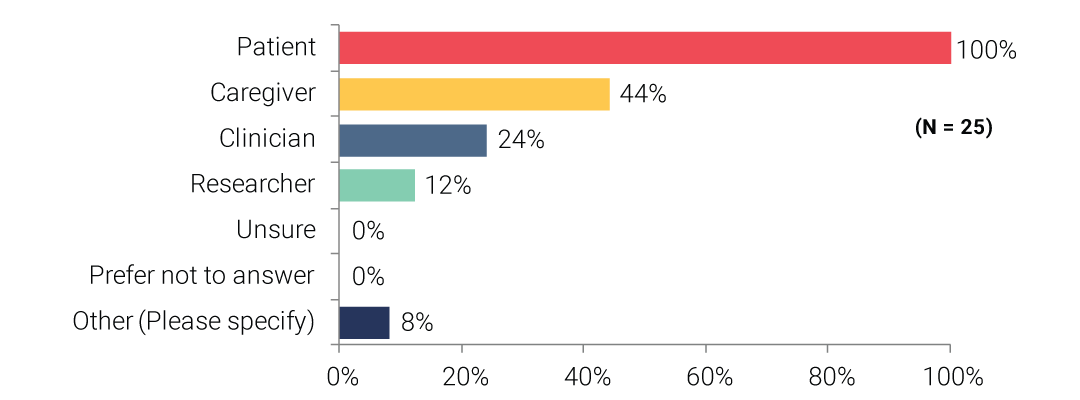

31) In your opinion, who should be the owner of a patient’s health information? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

All respondents (100%) think patients should be the owner of a patient’s health information and 44% believe the caregiver must be the owner. 24% chose the clinician as the owner and 12% chose the researcher. 8% chose other where one respondent stated that the organization that the patient gifted the data to should be the owner, while another respondent stated that the patient should be the owner, if 18 and over, and caregiver/parent/guardian should be the owner, if the patient is 18 and younger or over 18 and not mentally competent.

32) Do you think that your rare disease patients or caregivers have any cultural or religious beliefs that may affect their decision to participate in the database?

We asked this audience if rare disease patients or caregivers they are working/ involved with have any cultural or religious beliefs that might influence their decision to participate in the RARE-X database. 40% of the respondents were unsure, 28% chose no, and 25% chose yes. Some of the respondents who responded with yes explained their answers with quotes such as, “It’s a curse. Could be from a previous lifetime”; “cultural distrust of the system and pharma and government”; “institutional trust is a big issue with patients with rare diseases especially minority (non-white) patients”; and “it’s a matter of trust.”

33) Do you think that your rare disease patients or caregivers have any language concerns that may affect their decision to participate in the database?

Also, we asked this audience, if rare disease patients or caregivers they are working/involved with have any language concerns that might influence their decision to participate in the RARE-X database. (36%) responded with yes, (36%) responded with no, and (24%) were unsure. Respondents who chose yes explained their answers with quotes like: “understanding English and medical terms”; “understanding of consents and agreements and privacy laws”; “many who do not speak English have concerns about their understanding of what is being asked. Many of the language translation systems do not help with specific dialects”; and “the language must be in the patients’ preferred language, must be easy to read and comprehend, and the user interface must be easily understood for those less computer-literate.”

34) How would you like to access the database? (Select all that apply.)

Because multiple answers per participant are possible, the total percentage may exceed 100%.

71% of participants wanted to access the RARE-X database via a computer or a laptop, and 58% would like to access the database using a mobile app. 42% chose tablet, and 13% chose other, and one respondent quoted, “ I’d like to be able to have easy to use data extract functionality.”

35) Do you have any suggestions from your experience to ensure the success of the database?

44% of respondents had no recommendations on how to ensure the success of the RARE-X database. 24% were unsure and 28% chose yes and quoted recommendations, such as “allow people to choose what to share with whom, instead of an all or nothing. People may be willing to share some things but not others. As trust is built, they may be willing to share more”; “easily understandable information regarding platform in multiple languages that can be distributed among rare disease organizations”; “broad consent and it must be able to give information back to the patient/caregiver”; “establish trust with the rare disease foundations who can then be your allies in approaching patient community that they serve”; and “build the database with a ton of diverse patient/caregiver input. Some people don’t have access to laptops, tablets or phones. Some are visually impaired; some may not have the manual dexterity to type, some may need voice translation software if they can’t read or can’t type. Some caregivers have little time but want to contribute, so making it an easy and brief process would help. Some may want to contribute by answering questions over the phone but not entering data themselves.”

V. FOCUS GROUPS/INDIVIDUAL INTERVIEWS

INTERVIEW GUIDE DEVELOPMENT

The goal of the focus groups and individual interviews was to provide more insight into factors that affect DEI in the rare disease space. The guides (see appendix) were semi-structured, and questions focused on further understanding concerns, if any, among a variety of rare disease stakeholders (patients, caregivers, pharmaceutical representatives, researchers, clinicians, and patient advocacy group representatives). In addition, if concerns were identified, participants were probed to identify potential strategies that could assist in creating a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive rare disease space. Sample questions for focus group participants who identified as a patient or caregiver included: What is it like living with a rare disease (s)? Can you describe your role as a caregiver for an individual living with a rare disease (s)? What is a rare disease? How many rare diseases do you think there are? What does diversity in the rare disease community mean to you? Sample questions for focus group participants who identified as a pharmaceutical company representative or researcher included: How long have you been working in the field of rare diseases? What type of rare diseases does your company focus on? Sample questions for focus group participants who identified as a clinician included: How do you envision inclusivity in the rare disease community? Do you have any insights about inequalities in the rare disease community? Sample questions for focus group participants who identified as a patient advocacy group representative included: How would you describe the diversity among employees in your organization? What are the races/ethnicities of your coworkers?

Sample questions for individual interview participants who identified as a patient or caregiver included: What does equality mean to you? Do you have any insights about inequalities in the rare disease community? Where do you typically go for information and treatment for your rare disease (s)? Sample questions for individual interview participants who identified as a pharmaceutical company representative or researcher included: How does diversity, equity, and inclusion fit within your organization’s framework? Do you think your organization could further improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in your workplace? Sample questions for individual interview participants who identified as a clinician included: Have you ever experienced an instance when your rare disease patients or their caregivers didn’t trust you? How would you describe your rare disease patient’s caregivers’ comfort level using technology to access their healthcare? Sample questions for individual interview participants who identified as a patient advocacy group representative included: How would you describe the diversity of rare disease patients involved with your organization? In your opinion, what are some possible solutions to increase rare disease patients’ or caregivers’ involvement with patient advocacy groups? All interviews and focus groups were transcribed. Interviews and focus groups were recorded if an individual consented to a recorded session.

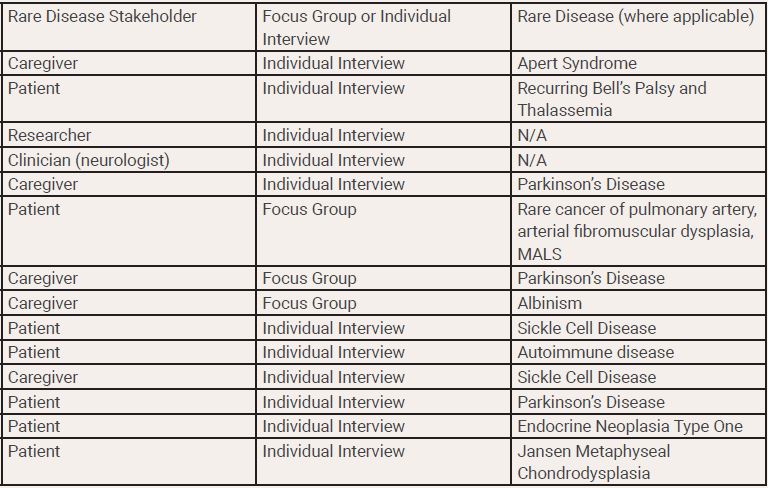

FOCUS GROUP/INDIVIDUAL ADMINISTRATION

We conducted a focus group (see appendix for focus group/individual interview guide) with rare disease stakeholders. We conducted one focus group with rare disease patients and caregivers (4 participated). We also conducted individual interviews with caregivers, patients, a researcher, and a clinician (13 participated). See Table 2 for more specifics on focus group and individual interview participants. Findings were used to develop the DEI recommendations for RARE-X. Focus group and individual interview responses elicited the following themes:

Table 2. Focus Group and Individual Interview Participant Information

Challenges/Barriers

Focus group and individual interview participants expressed the delay in identifying the presence of a rare disease. Specifically, they mentioned the gender biases that can oftentimes delay disease diagnosis. For example, one patient stated,

“When I started delving into it a little bit more…symptoms are migraines, they are high blood pressure, so they’re very innocent symptoms. If a woman appears in a doctor’s office with these symptoms, they’ll just give them medicine, and say you’re fine and send them home. And, unfortunately, a lot of these women end up having some problems because they treated the symptoms but not the disease. And they’re told that you’re stressed, you’re tired, you’re this and that, with no indication that you have a rare disease going on. And it’s never been investigated, so you don’t need to know. Maybe get a second opinion because you aren’t even alerted that might even be a possibility.”

Patients also identified resource related barriers and how this can delay the treatment for diseases. In addition, the lack of rare disease healthcare professionals results in travel and other additional related expenses. For instance,

“It does have a lot to do with insurance. With rare diseases, for me, it includes a lot of travel to far enough away places to get treatment and to get imaging. And if you don’t have insurance that will cooperate or you don’t have the funds to be able to travel back and forth for treatment that’s it—it cuts you out of that totally. You don’t have any local options for treatment for anything and that’s huge—it shouldn’t be that way.”

Other participants discussed the challenges related to technology, lack of access, and insurance barriers. One caregiver stated,

“Everyone doesn’t have access to technology…and some people are not as tech savvy with different things…I feel like there are ways around it. I know that we are heavily dependent on technology, but we went to the doctor, we picked up the phone and called them or we went there for our appointments. Now they have telehealth where you can do a virtual doctor’s appointment that way, but I feel that if you really want to do something like…she was saying she doesn’t have providers in her area that can do certain things for her, so she has to go to the bigger cities.”

In addition, others stated,

“Not everyone has access. Of course, you can go to your local library, but when you’re dealing with your healthcare, that’s more on a personal level. So, if you’re going to your local library to login to your portal, you want to be very careful. And if that’s your only means of accessing it, chances are you’re not going to use it. I definitely feel like there are some ways in which you’re affected simply just by your community and those things that are available to you.”

Others provided suggestions for lack of access to technology,

“I think trying to get the rare disease community involved in trying somehow to spread the word if people don’t have the technology, maybe in another way, even some sort of program on TV that people can access—that kind of thing.”

Lastly, patients expressed the challenges with insurance. One patient stated the following,

“I think that insurance companies are the biggest issue out here–of things that are not covered, things that we have to get on our own that they won’t provide, or they’re only going to cover at a certain percent. This is why healthcare is a big issue every year, every election. I do not think that they help support the things that we need.”

Education/Knowledge

Many participants also pointed to a need for more education and knowledge on rare diseases in general. When participants discussed the need for more education, they also expressed wanting to learn more to help others who may one day be diagnosed with a rare disease. For example,

“I’ve been doing a lot of research for my own sake, trying to advocate to get more doctors to have this on their radar, so that it does not come as a surprise to women when they find out that they have this disease and it has done damage to them that they didn’t realize was going on.”

There were other instances where participants discussed a clear lack of knowledge before they were diagnosed with a rare disease, understanding that this may be similar for other people in communities. One patient stated,

“I don’t think it’s been addressed enough. Before I had even been diagnosed with a rare disease, I don’t think rare disease was on my radar. I’m not even sure that I was aware there were rare diseases.”

In addition, participants started to discuss the lack of knowledge specific to their identified communities, equating this lack of knowledge to missing rare disease symptoms that can create a challenge later in their lives. A patient stated,

“I feel like in my community, the knowledge of rare diseases isn’t shared. You know, unless you are a victim of a rare disease or a close family member, you simply don’t know because it’s simply not talked about, the information isn’t shared. And I feel that puts us in a position where we probably don’t respond to symptoms as quickly as we should simply because we just don’t know. We’re sort of in the blind as far as what different rare diseases are, what the symptoms are. If it’s a common symptom, it often gets ignored even by the person who’s experiencing it because it’s something as simple as a headache, or I’m feeling tired, I just need to get some rest. I think oftentimes, especially in our community, we miss those important symptoms or those signs when we should probably catch them early or would catch them early if we were simply educated on the different types of rare diseases.”

Other points centered on educating everyone and not just individuals with rare diseases, hoping to promote concern among people in general. One participant suggested,

“Because we don’t have knowledge of what rare diseases may be, or we just look at one disease that covers everything, it separates people where they’re not concerned about these issues, they are overlooked in some cases. There needs to be more studies and information given out to people, so they are aware instead of overlooking rare diseases that affect everyone.”

Others discussed not just providing education on rare diseases but also ensuring people were aware of community resources to assist rare disease stakeholders. For example, it is important to provide equal access and opportunities to everyone who is marginalized within a minority group:

“It would mean providing opportunities to connect resources to people who can help you with opportunities that can move your disease forward–getting the right knowledge and information out to the outskirts of our population.”

Other patient participants discussed the challenges of being informed on their own rare disease diagnosis and how this can hinder their overall health. For instance,

“I feel like there’s not enough information out there… I have all these symptoms that I endure, and I feel like does this even connect to my rare disease or is this just some fluke?… There’s not enough information out there to let me know if what I’m experiencing is part of that rare disease, and I feel like there’s no cure, especially for this genetic condition. I know that they’ve done so much genetic variant testing with other rare diseases but there’s so many rare diseases that are missed out.”

Another patient stated the following,

“There’s also a lack of understanding. If you don’t understand enough about your own condition, then it can be very difficult to get care appropriately, and when things are rare, it’s hard to get information.”

Community/Support

An additional theme from the focus group and individual interviews focused on community/support systems and resources in general. For example, one participant stated,

“I think the other thing that you have to consider is that not everyone has a strong support system. In our case, we have different family members so that it’s a group of us and we take turns so the burden isn’t on one person. We take turns and because of my work schedule, I’m limited to only one day a week when I can assist. But having a strong support system even when you don’t have the doctors and the medical professionals reaching out to you like a caseworker of some sort to make sure that you’re aware of all of the things that are available to you–when you have a strong support system that can fill in that gap.”

Others pointed to the fact that many communities have limited access to healthcare providers and quality healthcare in general, stating,

“You have to look at your community as far as who has access to what they need. If you think about it, if you go to different areas of town, how many health departments are in your upscale areas versus your poverty-stricken areas, so it is the lack of what you have access to. And I think it does hit differently in different communities.”

Additional participants continued to express the need for support systems given the complex needs of many rare disease patients. For instance, one participant stated,

“Talking to other parents and to other people, parents of children with Apert syndrome as well as grown adults with Apert syndrome, makes a huge difference. Just knowing that, even though it’s rare, you get online and you get to talk to a lot of people who are dealing with very similar issues to yours, it’s very helpful. It’s comforting to know you’re not alone. It helps you to know what you might expect in the future.”

Another stated,

“I guess, in speaking with other people when I go for doctor’s visits, and just having a strong support system, and being a person that’s actually bound to win. If it wasn’t for that, I could be depressed, but right now for me, I consider it a medical annoyance, so I am just struggling right alone.”

Patient Registry

The project team also discussed strengths and challenges surrounding patient registries to identify what participants thought of as keys to increasing participation among all rare disease stakeholders. Many participants discussed being aware of patient registries and the benefits. For example,

“I was first diagnosed two years ago. I was presented with a packet to sign up for the patient registry for FMD and the doctor stated that it helps keep track of symptoms and to get an idea of the patients affected so that they can guide treatments for patients and also hopefully a blood test or cure.”

Other participants discussed having the opposite experience given the lack of knowledge of rare diseases in health care. One participant stated,

“I’m not sure that a lot of doctors offer that. If they happen to know the disease and know that you have it, they may be aware of a registry, but unfortunately, I think part of the problem with rare disease is that they didn’t realize there may be a registry to offer that patient to sign up for.”

Another stated,

“I don’t know. I’ve never discussed it with the doctors and they’ve never discussed it with us. So, I don’t know anything about that.”

Other participants stressed the regulatory factors of rare disease registries and the belief that patients should have access and control their own data. For instance,

“I think if a registry is to serve the community, that’s the part where I’m very opinionated and with the patient community. I do think that this kind of data and surveys belong to the families, and our health data belongs to us. And as a researcher, I am glad of the generosity that people share these with me. A good registry is controlled by families, or by the patients themselves and has all these things like security and privacy. A good registry is also in order to serve, I mean it’s not only for people to communicate with each other or to ask your own questions, but it is also to advance research and eventually, hopefully provide treatment and cure options for patients. That’s one of the main purposes.”

Many participants also stressed the need for diverse registries where all stakeholders are included in the process. For example,

“The more diverse we are in our registry, the more the cure or the treatment will be tailored not only to one specific group, and the earlier we can listen to the needs and desires of what patients want. So, the more the better, the more diverse the better. And maybe in the future if somebody else should ever have to run another study they will not have to choose only one select population because that’s all they can do and can find. So, I think that’s a really good reason to participate in registries.”

Others stressed the importance of registries for future generations. One participant stated,

“Well, they’re very important, particularly when you’re someone that has a rare disease or someone who has organ damage or a deficiency. Patient registries allow individuals to be connected and patient registries can save lives. Yes, we should because we need to know more. It’s helpful for our children and for our future.”

Another stated,

“Having data about my history, my experiences, geography is important, and I keep saying geography because location matters for a lot of reasons. Offspring is really important for a registry, to know if I have children and things like that. Blood typing.”

Other participants stressed registry characteristics that facilitate ease in participating in registries. For example,

“The registry needs to be translated into several languages. It should be easy, it shouldn’t be too complicated, not too much jargon, and must be easily accessed.”

Additionally, others stressed the importance of partnerships with rare disease stakeholders to encourage enrollment and participation. One participant stated,

“You need to partner with local hospitals because if I’m sick, if I’m in some local village, I’m not going to be reaching out to the foundation leaders, I’m going to be going to the hospital down the road, the doctor I know. So, reaching out to primary care, PCPs who are working with these communities and empowering them to share the registry. We know when they see patients that would be a much easier way to get more people registered.”

Equity/Inequity

Project staff also took the time in the focus group and interviews to focus on rare disease and the topic of diversity, equity, and inclusion. There was a clear theme related to prevalent equity and inequity within the rare disease space. Some participants discussed inequalities related to diseases that affect women. One woman stated,

“It’s been very difficult because I was diagnosed with fibromuscular dysplasia maybe a couple of years ago. It affects mostly women, healthy and young. It had gone unnoticed and undiagnosed for many years. The problem is because it is a women’s disease. I think that’s partially the issue of why it’s undiagnosed.”

Others discussed the lack of access to genetic testing due to inequities within healthcare. For example,

“I don’t know anything about genetic testing because I’ve never been offered genetic testing, nor do I know anyone in my immediate family or community who have been offered to participate in genetic testing.”

Others stressed the importance of recognizing economic differences and how they play a role in access to care. For example,

“I think socio-economics play a factor, because I think that if an individual has the access and the education and knowledge, they are treated better by providers, by doctors. And I think that if you have one sort of insurance or whatever the case, you are not offered the same care as someone that has a different insurance carrier.”

In addition, a participant stated,

“The inequities really have to do with access to healthcare and access to health professionals and the knowledge of those health professionals when it comes to diverse populations. The inequities…stand out a lot when it comes to information. Information can be a barrier when it comes to populations of people impacted by rare diseases and the information that allows them to understand what having a rare disease looks like and what it feels like for them.”

Participants also stressed the inequities in rare disease funding and research based on the type of disease and knowledge of it. For example,

“A lot of people put emphasis on the big diseases like diabetes and cancer when they’re not focusing on these little silent killers, such as these autoimmune disorders. There is where the inequity comes in because by definition it is a very difficult space to get treatments. There’s just not enough money so you’re definitely going to end up putting resources into diseases that are more prevalent than smaller populations.”

Others discussed the disparities in treatment access and referrals. For example,

“Also with having a rare disease, you can have some doctors that I don’t think they give you 100% of the treatment, and even if they can’t do it, especially what I know being in healthcare, they can refer you to someone that can help you instead of just sending you back out the door, hopeless.”

Others focused on discrimination against certain groups. For example,

“I think that sometimes there is discrimination against children. I know for a fact that some people don’t like to care for children or don’t like to care for different groups of people, and I’ve witnessed that, and that’s something that’s definitely a turn off, especially if you’re a parent.”

Research

In the focus group and interviews, project staff also focused on various aspects of rare disease. Many participants emphasized the importance of diverse researchers who understand or are interested in learning more about rare disease. For example, it was suggested that researchers

“come from a broad and diverse perspective of culture, not just education, but culture and education, culture and experience. It is necessary when you start talking about rare diseases and who will study them, how they will be studied and whether rare diseases are studied from the lens that impacts people based on diverse culture and geography.”

Others touched on barriers to participating in clinical trials for many rare disease patients. One participant stated,

“I think the problem is most research is done by research volunteers right? People that sign up to be in a study, and generally, people that don’t have a lot of socio-economic resources can’t sign up for those studies. They don’t have the time. They don’t have the time to fill out the surveys. They don’t have time to take off work to get to wherever the research is being done. And the thing is, a lot of people with rare diseases don’t have a lot of money.”

Many other participants focused on clinical trials and the recruitment component–making sure the inclusion criterion emphasizes diversity. One suggestion was to make sure participants in a rare disease trial mirror the diversity of the population that has that disease.

Lastly, participants emphasized the importance of trust and research and how the lack thereof influences their decision to participate in studies. For example,

“I don’t know if I would do it or not, or if I would even allow my uncle to do it because again, it just takes me back to Tuskegee, you know what I mean? So, we want to be included, but it boils down again to that shadow of distrust. I don’t know if I will be so readily open to do that.”

Additionally, a participant stated,

“Well, I think that’s going to always be because in the black community there’s always that just kind of hovering over you, that shadow of distrust when you’re dealing with medical information given to you. I just don’t take it and go with whatever they say, I am going to research it for myself. I mean that that’s just with anything, the lack of trust is just there and it’ll always be there until we are made well aware of what’s really going on.”

Another participant stated,

“It’s just from past experiences, even from other people in my community—the black community–where we feel the doctors don’t really listen to us or we are misinformed, uninformed, and pretty much ignored. That has been going on for years. It is pretty much embedded. Hearing these stories from friends and family that look like me and have the same race, you always second guess what’s being told.”

Yet another participant said they don’t respond to impersonal requests for research participation because they don’t trust someone they don’t know:

“The things that I participate in, there has to be more of a personal connection than so much just general, I don’t know who these people are, I don’t know who I’m giving information to.”

VI. FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the results from the DEI literature review, surveys, and the focus group/individual interviews, we recommend the following:

1. Create a resource guide for rare disease stakeholders. Potential topics could the following:

a. List of insurance providers that are beneficial to rare disease patients

b. Transportation options

c. Physicians who specialize in rare disease research

d. Physicians who specialize in rare diseases

e. Rare disease from a financial standpoint

f. Insurance coverage in general

g. Education of family members

h. Access to care for individuals with minimal to no insurance

i. General support

j. Social media rare disease groups

k. List of diseases that predominantly affect minorities

l. Repository of scholarly journal articles as a resource for patients

2. Provide education for rare disease stakeholders that addresses the following:

a. Securely accessing your medical record or other personal information using technology

b. How to use telehealth

c. Benefits/challenges in using telehealth

d. Technology in general

e. Genetic testing

f. Cultural competence

g. DEI for rare disease stakeholder’s staff, patient advocacy groups, volunteers, and any other relevant stakeholders

h. Explaining the importance of rare disease registries and how they provide valuable information.

i. Clinical trial process

j. Research study process

k. Intentional recruitment strategies for addressing diversity

l. Effective strategies to access quality healthcare

m. Health literacy

n. Registries

3. Create awareness campaigns (posted on a website, social media, etc.) that address the following:

a. Descriptions of rare diseases that predominantly affect women

b. Tips for effective communication for healthcare providers and women

c. General knowledge of rare diseases

d. Targeted campaign for minority communities to raise awareness of rare disease in general

4. Partner with medical schools to increase interest in physicians who practice in rare disease.

5. Partner with medical schools to broaden the scope of rare disease information for students.

6. Create a support resource network for rare disease patients that includes physicians, other relevant healthcare professionals, case workers, etc. to assist with connecting patients to the right information to continue to further their care (access to technology).

7. Partner with school systems to provide educational resources on rare diseases, introducing them to topics via focus groups, class discussions, etc.

8. Provide information pamphlets for the general population, patients, and physicians on rare diseases that predominantly affect children.

9. Provide patients with a resource so they can track their appointments, information related to their rare disease, etc.

10. Create a resource that allows patients to keep track of their health information and other important information for their rare disease.

11. Create an educational TV program or beneficial resource about rare diseases for people who don’t have access to the internet.

12. Provide a checklist for physicians on referral processes for patients with rare diseases to include genetic testing, registries, natural history studies, etc.

13. Provide training that discusses mistrust in healthcare for minorities. Sample topics to include treatments, proper referral process, genetic testing.

14. Offer live translators, mobile translation, devices that help with translation, and/or identify potential resources.

15. Partner with a physician that is familiar with your disease who can assist with research.

16. Provide additional telehealth opportunities or additional mechanisms of accessing healthcare where available.

17. Provide information pamphlets for the general population, patients, rare disease stakeholders, and physicians on rare diseases that predominantly affect women.

18. Hire a diverse staff (medical professionals, health professionals, public health experts, etc.).

19. Fund racially, culturally, and ethnically diverse researchers to engage diverse populations in a very intentional way.

20. Disseminate research findings with research participants.

21. Hire diverse staff, volunteers, board members, and other rare disease stakeholders.

22. Provide lay documents of research and other resourceful rare disease information.

23. Explain treatments, medical record, etc. to patients to offset mistrust.

24. Prioritize the funding of rare diseases specifically ones that affect minorities.

VII. CONCLUSIONS

Diversifying the rare disease space is essential for continued success in combating inequities in the rare disease field. Initiatives fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion provide an opportunity to expand culturally competent health care, boosting innovation for future therapeutics. Ensuring DEI within rare disease can be tedious and large in scope, requiring focused program implementation that effectively engages all stakeholders. Our findings indicate the importance of providing information on rare diseases that predominantly affect women, creating campaigns that raise awareness on how to effectively communicate with physicians and patients, and partnering with medical schools to increase interest among students to specialize in rare diseases, among others.

VIII. REFERENCES

Amorrortu, R. P., Arevalo, M., Vernon, S. W., Mainous, A. G., 3rd, Diaz, V., McKee, M. D., Ford, M. E., & Tilley, B. C. (2018). Recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities to clinical trials conducted within specialty clinics: an intervention mapping approach. Trials, 19(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2507-9

Andersen, T. (2012). The political empowerment of rare disease patient advocates both at EU and national level. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 7(Suppl 2), A33-A33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-7-S2-A33

Baynam, G. (2015). A diagnostic odyssey-red flags in the red sand. Medicus, 55(9), 40.

Boston Medical Center. (2021). Ethnic Based Genetic Screening: Know Your Risks & Your Options. https://www.bmc.org/genetic-services/ethnic-based

Boulanger, V., Schlemmer, M., Rossov, S., Seebald, A., & Gavin, P. (2020). Establishing Patient Registries for Rare Diseases: Rationale and Challenges. Pharmaceutical Medicine, 34(3), 185-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-020-00332-1

Budych, K., Helms, T. M., & Schultz, C. (2012). How do patients with rare diseases experience the medical encounter? Exploring role behavior and its impact on patient-physician interaction. Health Policy, 105(2-3), 154-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.02.018